Clearing a Safe Path

Highway safety professionals are continuously trying to improve practices for Traffic Incident Management

The night of Nov. 18, 2016, Utah Highway Patrol trooper Eric Ellsworth responded to a call about low-hanging power lines on a rural two-lane highway about an hour north of Salt Lake City. At the site, Ellsworth, 32, parked on the side of the road, according to The Salt Lake Tribune, and shined his vehicle’s spotlight onto the electrical cable so drivers could see it, knowing it could be problematic for high-profile vehicles.

A semi approached, and Ellsworth stopped the truck to prevent it from catching the cable. As he approached the driver, an oncoming car struck and critically injured him.

Five days later, Utah Highway Patrol Colonel Michael Rapich typed an email to his colleagues about Ellsworth, a second-generation Utah trooper, seven-year veteran of the force and the father of three young boys: “Late last night, after a long fight, he succumbed to his injuries surrounded by his family and fellow troopers.”

In his 28-year career with the Utah Highway Patrol, Rapich has lost seven troopers in line-of-duty deaths. Three, including Ellsworth, occurred in what the force calls “struck-by” incidents, in which a trooper was struck by another vehicle while actively involved in a traffic incident.

“Probably the most frustrating part about this accident with Eric is that it was a low-risk traffic incident on a rural highway with a very low amount of traffic,” Rapich says. “And then, just in an instant, it went from almost a non-issue to a tragic event.”

After every incident, Rapich says, he takes a hard look at what the force and the individual could have done differently, and which hazards they could have mitigated to possibly change the outcome. In many cases, it’s a matter of just inches that makes all the difference.

“Every single [traffic incident] has the potential for something really horrible happening if we’re not taking every opportunity to mitigate the risk as much as we can,” he says. “And even when we do, things happen. The big takeaway is that every traffic incident is still a high-risk environment.”

“TIM has changed the way we go about doing our business, and I think it’ll change and save lives going forward.”

– Colonel Dereck Stewart, Tennessee Highway Patrol

TIM to Prevent Secondary Crashes, Save Lives

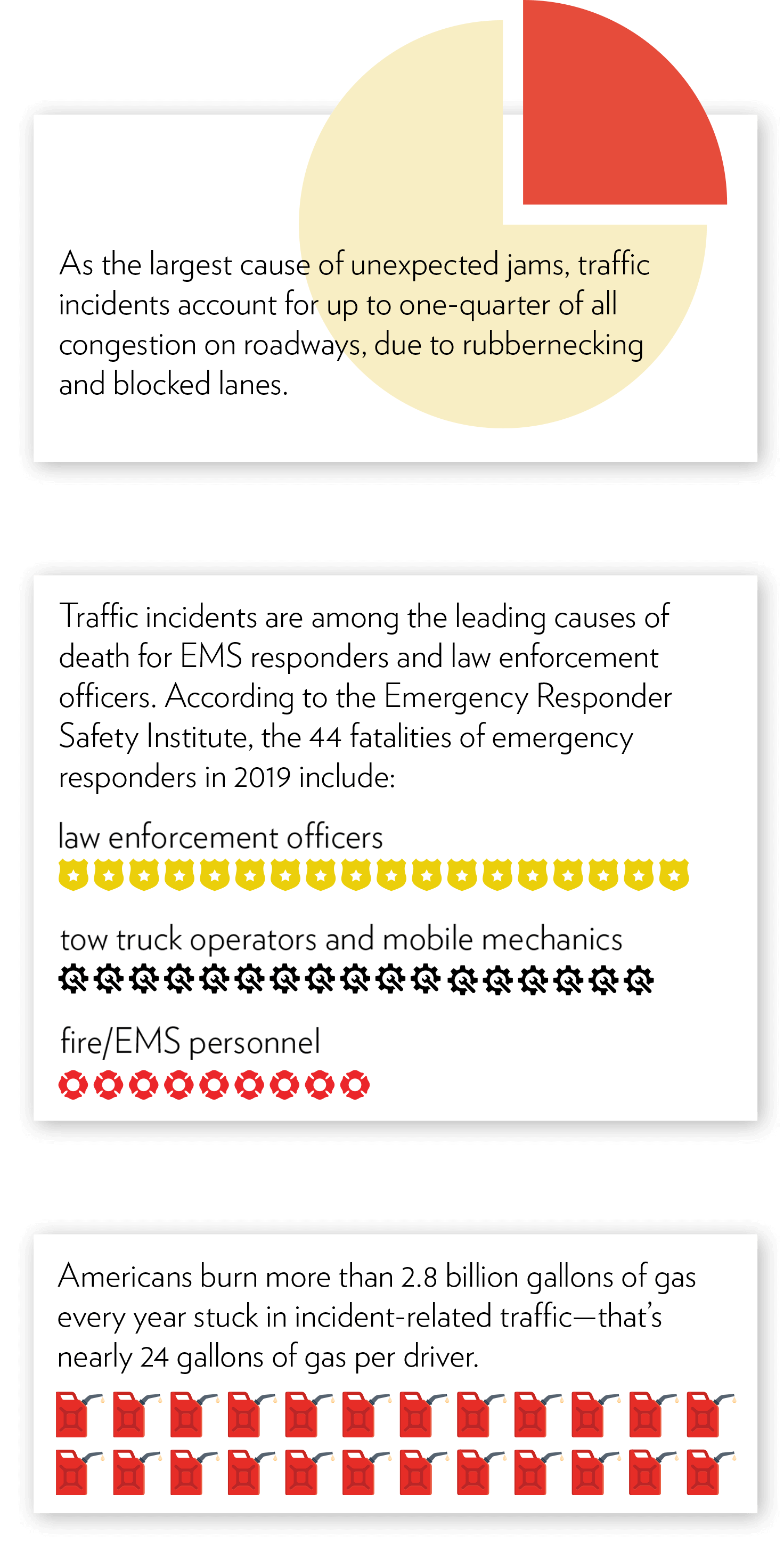

Each year, an average of 6 million crashes kill more than 30,000 motorists and injure an additional 2 million, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). That number is growing, as is the number of related first responder deaths.

“Until we can get these figures to zero, there will be a profound need for traffic incident management (TIM) training,” says Mark Kehrli, the director of transportation operations for the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), a division of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

TIM focuses on detecting, responding to, and clearing traffic incidents so that traffic flow can be restored as safely and quickly as possible. Effective TIM reduces the duration and impacts of traffic incidents and improves the safety of motorists, crash victims and emergency responders. Partners include law enforcement, emergency medical services, and fire and rescue.

The FHWA first created a TIM-focused team nearly 20 years ago and has since made TIM training a priority nationwide. The agency has held three Senior Executive Transportation and Public Safety Summits to discuss ways to improve traffic incident management and responder and motorist safety. As of March 23, 2020, nearly 470,000 responders have been trained; FHWA’s goal is to reach one million.

Kehrli stresses the importance of using TIM to save lives and prevent secondary crashes, such as the incident in northern Utah. “First responders face an increased risk of being fatally struck or severely injured by what we call ‘D-Drivers,’” Kehrli says. “Drivers who are distracted, drunk, drugged or drowsy.”

In addition to helping decrease fatalities and injuries, TIM also fights the rising cost of these incidents, which has sharply increased, according to the American Automobile Association (AAA). The cost of a fatal crash is $6 million, and an injury incident is $126,000, both up by 85% over a four-year period. The costs include lost earnings, medical expenses, emergency services, property damage and travel delays. As good TIM practices are gradually being put into action, trainees across the country are reporting improvements in overall safety at traffic incidents.

A team approach

Nearly three decades ago, when Rapich began his career in law enforcement, he learned a fundamental principal of traffic safety that he carries with him today in Utah: “Whatever is happening, whatever the incident, get there and put things in place immediately to stop it from getting worse,” Rapich says. “That’s the number one thing we do.”

The National TIM Responder Training program has been completed in all 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico by personnel including DOT employees, police, tow truck operators and fire rescue/EMS teams. The first responders learn recommended practices for safe and efficient incident mitigation, such as best practices for towing and recovery; “authority removal” laws, which remove liability when taking wrecks off the road; and uses of helpful cutting-edge technology such as drones.

“We can’t stress enough the importance of first responders and agency leaders becoming educated on TIM, and requiring its training within their organizations,” Kehrli says. “It saves lives, and is one of the most important resources available to the first responder community.”

Colonel Dereck Stewart of the Tennessee Highway Patrol said since the state began implementing TIM initiatives in 2014, it has become a mainstay of their operations.

“The program addresses a number of goals,” Stewart says. “We’ve expanded TIM to go beyond law enforcement and include partners such as the towing industry. Every training opportunity we have now, they have a seat at the table.” Prior to TIM, Stewart says, all the first responders would show up to a crash scene, each with their own protocol. “Now that we’ve come together as one, it’s more of a team approach and an opportunity to improve the safety not only of our responders but the community and the customers we serve every day.”

Stewart says he would like to improve TIM education to other stakeholders, which will further increase safety and decrease the time spent at the scene of an accident. Various channels will reinforce the message—including social media, statewide outreach and visits to schools, where troopers occasionally talk to students, reminding them not to drive distracted and what steps to take if they’re involved in a crash.

“TIM is needed and necessary,” Stewart says. “It has changed the way we go about doing our business, and I think it’ll change and save lives going forward.”

In Utah, Rapich reminds troopers that as soon as a traffic incident occurs, it starts impacting traffic. “That creates congestion,” he says. “It’s going to back up far beyond what you can see at the scene, and that has the potential of causing devastating consequences behind you, as well as what you’re dealing with right there.” He says TIM training reinforces three priorities at a traffic incident: safety (of victims, motorists and first responders), time delays (even a small traffic incident in a high-volume area can create two-hour delays) and economic impacts (productivity loss can mean delayed workers, late deliveries, environmental effects or air quality impact).

One of the prevailing philosophies within TIM is that if an incident can be moved from a high-traffic environment, move it. Whether it’s a broken-down motorist or a crash, Rapich asks his troopers: “Do you need to be there?” Getting first responders and victims out of the high-risk environment, he says, alleviates concerns about the three priorities almost immediately.

“From the minute dispatchers get the call about a crash, they will ask if the drivers have the ability to get off the freeway,” Rapich says. If so, the motorists drive to a safer, predetermined location, where a trooper meets them. “We don’t have our officers or first responders in that hazardous environment. We don’t have the victim in that environment anymore. We’re not impacting traffic. And we’re not creating delays or situations for something else to happen.”

If responders can’t avoid being in a high-risk environment, they use TIM procedures to quickly evaluate the scene and do whatever necessary to make it safe. That includes ensuring the right responders arrive at the right location, taking an extra lane, slowing traffic, setting up an early warning for oncoming drivers, providing emergency medical aid until help arrives and clearing the crash path, especially in icy conditions (if one car slid on an icy spot, another vehicle may follow the same path).

Rapich says all the components of TIM—including training first responders, pushing out the message internally, and educating the public through mainstream and social media—have been “absolutely effective” and that increasingly, responders and the public understand the risks of associated traffic incidents. Rapich says although they’ve made progress, they’ll never be able to “check the box” and stop worrying about TIM. “It’s an infinite [challenge],” he says. “If you’re involved in traffic management, it’s something you’re engaging in every single day.”

Each year, an average of 6 million crashes kill more than 30,000 motorists and injure an additional 2 million, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). That number is growing, as is the number of related first responder deaths.

Each year, an average of 6 million crashes kill more than 30,000 motorists and injure an additional 2 million, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). That number is growing, as is the number of related first responder deaths.